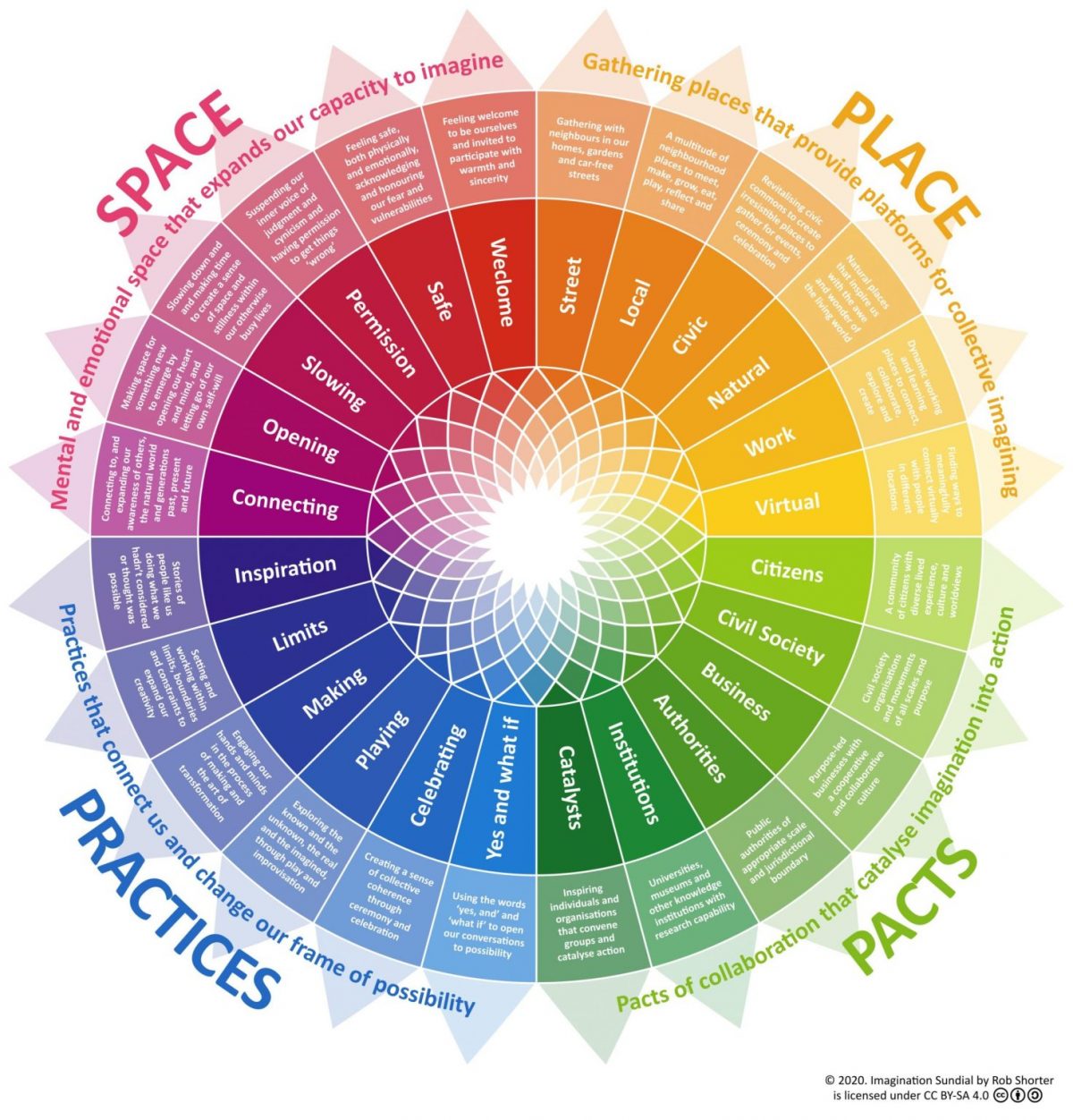

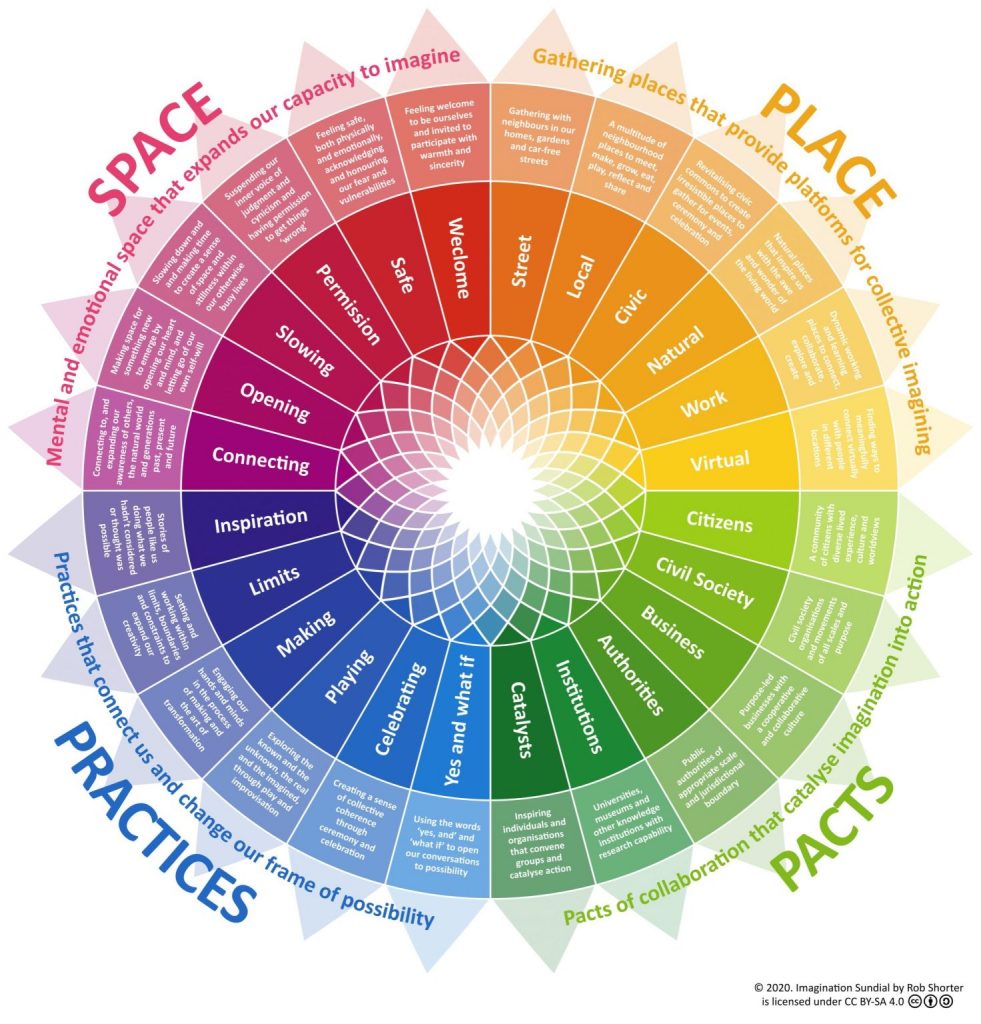

The Imagination Sundial

By rob hopkins 19th July 2020

Rob Hopkins and Rob Shorter introduce The Imagination Sundial.

First published by Rob Hopkins in June 2020.

Whilst finishing his Masters at Schumacher College and researching his dissertation last spring, Rob Shorter came to stay with us as our lodger. He had been inspired by a workshop I had given at the College about the power of What If that had initially prompted him to explore the power of the words ‘what if’ at the school climate marches (a story I reference in the Afterword of ‘From What Is to What If’). Whilst doing this project however, something interesting struck him:

“although some children were forthcoming, others were more reserved. Similarly back at the College […] we observed a difference in people’s receptiveness to imagine corresponding to the different qualities of meetings. There were clearly factors at play that were impacting people’s capacity and willingness to imagine.”

It was an insight that ended up prompting his dissertation, which was an exploration into the conditions that cultivate the collective imagination, framed within the context of re-imagining economics.

It was also around the time that I was putting the finishing touches to ‘From What Is to What If’. Drawing on ideas in the book, along with his own fieldwork, interviews and conversations we had together, he pulled together a framework of elements that has now evolved into the ‘Imagination Sundial’ that we are sharing with you here.

We know it’s only part of the picture, as one could never hope to capture the full unknowing wonder that is the imagination. But it’s often the part, when shown in talks, that people take photos of or ask for afterwards, and so we thought we would introduce it to you and its main elements in the hope that it is something you may find useful.

What it aims to capture

The aim of the Sundial is to act as a heuristic or design tool for how we might set out, intentionally and skilfully, to rebuild the imaginative capacity of people, organisations or nations. Underpinning this is the belief, as set out in ‘From What Is to What If’ that we are living in a time of imaginative decline at the very time in history when we need to be at our most imaginative.

This decline has been noted by various researchers, and its implications are profound but rarely discussed. We believe that this decline is first and foremost underpinned by the rise in trauma, stress, anxiety and depression which, neuroscientists have shown, cause a reduction in the hippocampus, the part of the brain most implicated in imagination. Other factors, such as our interactions with social media and digital technologies, the declining amounts of time we spend outdoors, the decline of play in our culture and the sidelining of imagination in our education system also all have a role to play.

If imagination is, as John Dewey defined it, “the ability to see things as if they could be otherwise”, and given that we need to see, as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change put it, “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society”, then nurturing the capacity, across a population, to have the most resilient and dynamic imagination possible is vital.

The Sundial contains 4 main elements: space, place, practices and pacts. What we aim to do here is introduce each of these to you, along with some examples that nicely illustrate them in practice.

Space

The mental and emotional space that expands our capacity to imagine.

Space is foundational to imagination. Busy and stressful lives riddled with fear and anxiety inhibit our potential for imagining, so space is about how we can slow down, open up and connect with others and the natural world to rekindle this capacity. It’s also about how we feel welcome and safe to participate when we gather together and give ourselves permission when we’re scared of getting things ‘wrong’. Space fluctuates day by day. We can have good days and bad days. Moments where we’re more imaginative and moments where we struggle. Space is like the soil of imagination. The more we cultivate the soil, the better the imagination grows.

We suggest that it also involves a deliberate process of making space within our own lives for something to emerge, and we recognise that imagination, to a degree, is a function of privilege, in that it is very hard to live an imaginative life when your basic needs aren’t met and when you are stressed or in trauma. We recognise the impacts of colonisation, in that colonisation and exclusion based on race, gender, class or sexuality determine whose imagination actually gets to shape and determine the future of a particular place. As Adrienne Marie Brown puts it:

“We are living in the ancestral imagination of others, with their longing for safety and abundance, a longing that didn’t include us”.

We also recognise that austerity can be seen as an attack on a population’s ability to live richly imaginative lives. As such we argue that we need to reframe strategies such as a Universal Basic Income or a 3 or 4 day week, for example, as being vital imagination strategies that give people much-needed space in their lives which could be vital to making space for more imagination.

Here are a few other examples that help cultivate space:

Morning pages is a practice from Julia Cameron in ‘The Artist’s Way’, initially designed to help people with artist’s block, that has taken off in popularity since first published in 1992. It is a daily individual practice of continuous freefall writing of three sides of paper every morning of whatever comes into your mind. The process is designed to empty your head of whatever is there; thoughts, reflections, fears, worries, anxieties, hopes and whatever else might arise. The intention is not to filter anything and through this you begin to notice what might otherwise go unnoticed. And it’s this noticing that helps you intervene and take action on any unhelpful thoughts, instead reminding yourself of the various positive affirmations you have written for yourself.

‘The Time Machine’ is a creative activity (described in more detail here) that invites people to slow down, close their eyes and use their imagination to travel forward in time 10 years, into a future where in the intervening 10 years, everything that could possibly have been done was done, a period of remarkable and deep transformation. It invites people to use their imagination with all of its senses to explore what such a future would look like, feel like, smell like, sound like. It has proven very powerful in groups of a range of sizes. It allows the participant to create what researchers Jackie Andrade and Jon May call ‘memories of the future’.

The Children’s Fire is the name for a flame that is lit at the start of a meeting, people’s assembly or any other gathering of people that will be making decisions that could impact the future. The Children’s Fire represents all life on earth and the next seven generations. It serves to remind us that every decision we make is not just ours to carry, but will be left for seven generations to come. Two minutes silence is taken to allow those present to contemplate not only the next seven generations of human life, but all of interconnected life on earth that we must act in awareness of.

Milling Around is an activity for starting a workshop where you’re invited to mill around a room in between each other, noticing who’s there with you. The facilitator of the exercise then asks you to find yourself standing in front of someone and share the answer to a question that the facilitator offers that might relate to how you’re feeling or a question that has something to do with the reason you’ve all gathered together. This is then done about three times so you’ve spoken with three people answering three different questions. It’s a very effective exercise in creating connections in a short space of time and it can dramatically shift the collective dynamic to a slower, more connected and empathetic place.

Place

Gathering places that provide platforms for collective imagining.

“Like a snail needs a shell, like a fox needs a den, like a bird needs a nest, human beings need a sense of place, but not just a sense, they need a gathering place at every single scale of their community” – Mark Lakeman: Badass democracy: reclaiming the public commons

What mental and emotional space is for the mind and soul of an individual, so place is for the mind and soul of a community. These are places to dwell and enjoy without having to buy or pay anything. Places designed for connection, creation, collaboration and chance encounter. Places that are welcoming and inviting to a rich diversity of people. And perhaps most importantly, the best places are those that you leave with your sense of what the future could be having changed, even by a small amount. But places like these where you don’t have to buy or pay anything have reduced in number as former public commons have been enclosed by private ownership. If we’re to rebuild the collective imagination, we need to start reclaiming and rebuilding the commons at every scale of community, from the street to central civic places and the wild natural places around us.

Here are a few examples of wonderful place-making:

Urban agriculture projects such as Prinzessinnengarten in Berlin, now one of the city’s main tourist attractions, are a good example of this, as is the work of Pre Saint Gervais en Transition in Paris who are campaigning for the creation of an ‘urban forest’ in their neighbourhood. These places can also be natural places, and the ability of such places to stimulate the imagination as well as to generate awe, in turn shown to increase empathy, generosity and pro-social behaviour, has been well documented.

Places can also be the places we work, study, relax or worship. In Los Angeles, Transition Pasadena worked with the local Throop Unitarian Church to transform their sunbaked landscaping using xeriscaping into a beautiful drought-resistant garden, and found that wedding bookings at the church increased hugely as it was now a far better backdrop for wedding photos! The church also became home to many Transition activities such as their popular Repair Café.

Sometimes these places can be mobile, such as Encounters Arts’ ‘Chrysalis’, a mobile ‘cabinet of curiosities’, designed specifically to evoke the curiosity and imagination of whichever community it visits. And as many of us have found during the COVID-19 lockdown, with some creativity and thought, even online places can do an amazing job of stimulating the imagination.

In Portland, Oregon, Intersection Repair invites residents who live around a shared intersection to come together to imagine what they want their street to look like, then collectively paint the road surface. The results are truly beautiful and it starts to change the way people see the place. Communities start holding street parties, setting up mini libraries and just generally gathering in the place they once ignored.

Starting in Dallas, Texas, and now having spread across the US and internationally, the Better Block project is a great example of what we have come to call ‘Pop Up Tomorrows’, i.e. that we can take a place people know well and pass every day, and give it a makeover so that it becomes an immersive, living, breathing expression of what a low carbon, more just and equal future would be like to actually live in.

And finally, one of the delights of the Transition movement is that there are now places that have been doing Transition long enough, and with sufficient determination, that they now exist as a place that tells a powerful immersive story to visitors of how the future could be, places such as Ungersheim in France and Liège in Belgium. These places are precious, and their ability to inspire the imagination should not be underestimated.

Practices

Practices that connect us and change our frame of possibility.

Whilst space and place set the foundations for imagination, practices is where the magic really happens. Practices are the things we can do together that take us out of our rational thinking minds into something altogether different, breaking down our internal constraints and societal norms to open up a greater sense of what is possible. A good practice creates bridges between the real and imagined, the known and unknown, inviting us into the liminal space where things begin to shift. This can happen through play, through making and through stories. It can happen through the use of limits and through exploratory language like ‘yes, and’ and ‘what if?’. Great practices also cultivate mental and emotional space and some even create places in the process, thereby ticking all the boxes for imagination.

Here are a couple of our favourite activities:

Transition Town Anywhere is an activity developed by Encounters Arts in association with Transition Network, where a group of people, having imagined themselves travelling forward to a 2030 where the UK had successfully become a zero carbon, fairer, more equal and biodiverse society, then imagine what they would be doing in such a future, what their role would be (described in more detail here). Then, through a carefully facilitated sequence of exercises, they end up building, in 3D, using cardboard, string, bamboo canes, sticky tape and pens, a living, breathing settlement in which they then trade, celebrate, talk, share, plan, eat, connect. It can be a very powerful exercise for giving people a lived experience of how the future could be. It speaks to the powerful role of hands-on making, and of the analogue – real things made with our hands – and how important it is to not see this as a challenge where everything can be done digitally.

Asking good ‘What If’ questions: there is much exploration in ‘From What Is to What If’ about the art of asking a good What If question, as well as examples from around the world. A good What If question opens up a range of possibilities in a positive and hopeful spirit. It is sufficiently open-ended that it doesn’t feel prescriptive and it allows people to shape their own creative responses. We argue that mastering the art of asking good What If questions is something that is vital to skilful strategies for the next 10 years.

Pacts

Pacts of collaboration that catalyse imagination into action.

One of the best catalysts for the imagination is action. Action instills belief, and belief inspires further action, and a great way to bring about action is with pacts. A pact is an agreement that recognises multiple actors in a place have to come together to make things work. They are the result of collaborative and cooperative relationships cultivated between public authorities and citizens, along with local business, knowledge institutions (like universities) and civil society organisations. A part of this is the role of the catalyst, the individual or organisation that performs the skillful act of inviting, convening and offering the initial vision. Everyone plays a part in the pact. And rather than compete, the strengths of each actor is combined with the others, meaning pacts have a truly transformative potential for translating the collective imagination of all actors into action.

The idea of pacts were inspired by the amazing work of the Civic Imagination Office in Bologna, Italy, who work with communities across the city through 6 ‘labs’, using visioning tools and activities to come up with a diversity of ideas for the future of the city. When good ideas emerge, the municipality sit down with the community and create a pact, bringing together the support the municipality can offer, and what the community can offer. In the past 5 years, over 500 pacts have been created.

Pacts feel important because without them, or something like them, we are nurturing and inviting the imagination of people and of communities, but then not meeting them halfway. The creation of pacts is fundamentally respectful, meeting the imagination in the middle and giving it a helping hand to become a reality. Pacts can be made at any level. Any organisation deciding to undertake work around nurturing imagination must design into the process a willingness and an openness to turn ideas that emerge from the imagination process into a reality via the use of pacts. It is the key ingredient often missing from discussions around imagination.

How to use the Sundial

We offer this model in the hope that you find it useful. It distils insights from both of our work and thinking in a form whose usefulness and relevance will be determined by your experience of it, and how helpful you find it in your own work.

It feels to us that it could be used just as effectively over a range of scales, from small community groups to organisations, to movements to institutions, to the basis of a national imagination act. And it’s something Rob Shorter hopes to put to use within his new role as Communities Lead at Doughnut Economics Action Lab that launches in September.

But we’d love to hear from you. What do you find useful here? What do you think is missing? And how might you make use of it? We would love the evolution, the next iteration of the Sundial, to be richer and deeper and a weaving together of our shared experience, so do share any thoughts you might have as to how we could make it into a more useful and impactful tool.

Rob Shorter and Rob Hopkins. June 2020.

You can download a higher resolution pdf of the Sundial here.

© 2020. Imagination Sundial by Rob Shorter is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0

1 Comment

Rob, I’m sending pictures to you of sundial items, can’t do that here. This is very dense, it’s hard to write about it without delving and cutting, rearranging, to understand what is the overall story here? You may be trying to do too much.