Transition and the Commons: freeing our imaginations

By rob hopkins 7th December 2016 Culture & Society

On 16 November I was in Brussels for the first European Commons Assembly: a gathering of over 100 people from all over Europe and beyond who are stepping forward to make visible, manage and protect the resources that we as citizens hold in common. We held our session in the European Parliament, hosted by members of the Inter-Group on Common Goods: MEPs who have formed a new working group that will include strategy on the commons in political debate. This is a milestone: the meeting of these two separate groups for the purpose of proposing policy that could be enacted across EU states sends out a number of signals.

"Only the purpose of a coherent community, fully alive in both the world and in the minds of its members, can carry us beyond fragmentation, contradiction, and negativity, teaching us to preserve, not in opposition but in affirmation and affection, all things needful to make us glad to live".

American poet and ecologist Wendell Berry

One is a call to those working in this space (and the Commons is all about spaces) that the work we are doing to protect our water, soils, fisheries, public spaces, shared knowledge, local food and energy production and digital networks is seen and valued. Another is that the transition to sustainable living, to itself be sustainable, is being called to grapple with issues of governance and law so that we can build frameworks that uphold and validate our work.

A third signal is simply that all the shared ideas and language around the Commons offer a lively, inclusive space in which we can find Eco-Villages, the Internet, Permaculture, municipalities and mayors, mapping, Community Land Trusts, local Democracy, Transition, farmers, housing co-ops and the many facets of this movement. A movement that now appears to be moving in from the margins as more people realize that whole-systems change takes all of us to join in.

So what is the Commons? I’m going to make a quick backtrack for those of you curious to know more. In Europe we first hear about the Commons from the Roman Emperor Justinian who in 535 AD placed res communes (shared things) in the body of law he drew up. “By the law of nature these things are common to mankind—the air, running water, the sea and consequently the shores of the sea”.

Here in the UK, and in much of the western world, our law is based on Roman law, which is essentially about property. The commons are documented in the historical record when they but up against enclosure. Famously the Charter of the Forest, issued in 1217, two years after Magna Carta, gave common people access to the hunting ground of the King for activities from which they could gain a livelihood. Commoning (exercising those activities) kept the Commons alive, and still does.

The Forest Charter’s 1st Chapter saved common of pasture for all those “accustomed” to it. The 9th chapter provided agistment (pasturing of livestock) and pannage (pasturing of pigs) to freemen. The 13th stated that every freeman shall have his honey. The 14th chapter said that those who come to buy wood, timber, bark or charcoal and carry it out in carts must pay chiminage (a road tax) but those who carry wood, bark or charcoal on their backs need not pay chiminage.

I have focused on the rights relating to wood because wood in the Middle Ages was ubiquitous: it fuelled the economy, it shaped the architecture, it literally underpinned the culture. It was present in every aspect of life and dominated the life-supporting ecosystems of Europe. Fast forward to Standing Rock and you can see that the way indigenous peoples care for precious resources is akin to commoning, and that the market (rather than a king) is seeking to further enclose not just land but the whole Sioux culture. And the driving force now is oil.

We got into small groups during the Assembly to share what The Commons means to us, and I jotted down some of the answers: “Moving from I to We: the big problems we have are in common, we need to solve them in common.” “All those things that are not owned or enclosed: knowledge, water, the soil, the air….” “Those natural resources that support life on earth and that we all share”. “The commons expands civic space and the concept of what it means to be a citizen.” “They are reservoirs of bio-diversity”, “empowering community renewable energy”, “things that need to be excluded from the market because they are so vital to life”.

The EU Intergroup on Common Goods names “co-ops providing care for elderly in the neighbourhood, Greeks cooking for their crisis-struck neighbours in social solidarity initiatives, or collaborative production endeavours such as Wikipedia made possible by new technology”. And adds: “in discussions on climate change, on common ownership of water and in discussions on social justice, people have started appealing more to the concepts of ‘the common good,’ ‘commons’ or ‘public goods’ – all in parallel to the use of human rights. Surely the human rights discourse remains the most powerful social justice language we have, importantly enshrined in international conventions. With the concepts of the commons and common goods also gaining political traction our emancipatory spectrum is now being broadened. Tellingly, this discourse has now also reached Brussels.”

While in the Parliament we heard three policy proposals presented, Democracy as a Commons, Community Land Trusts (housing), and open technology for a Digital Commons. Altogether the collective of groups and individuals in the Commons Assembly prepared 26 proposals that are still being worked on for future submission.

These range from scientific commons and citizen science, the Commons and the solidarity economy, and currency as a commons to education, energy and knowledge. If you want to join in, please go to the European Commons Assembly website. At a time of deepening political upheaval I was heartened to read in the call that the European Commons Assembly put out that “we consider ourselves active and cooperative citizens caretakers working for healthy and fair neighbourhoods, cities and societies”.

What does Democracy as a Commons look like? We were reminded that Iceland crowd-sourced a whole new constitution. In Madrid, citizen candidates of popular unity won the election for the city administration. In Belgium the G1000 Citizens Summit had over 1000 people deliberating chosen topics. How can we scale these processes up? At local level, citizens can share power and promote public debate, organising their own civic discussions and inviting politicians to come and listen. At national level, we could demand a legal structure for citizen organising. And at municipal level we were reminded that in Bologna the Regolamento or Regulation on public collaboration for urban commons has enabled the community to take responsibility for its common good, creating a new dimension of the urban commons.

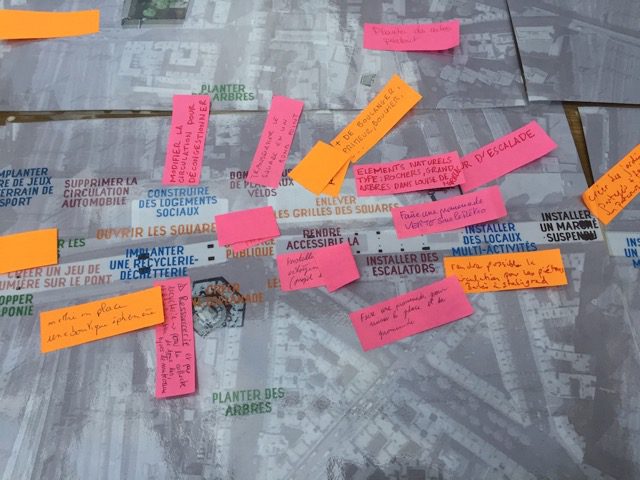

I saw an example of urban space in the process of becoming a commons when I was in Paris immediately before the Commons Assembly. As a co-founder of the Community Chartering Network I was work-shopping charters for community governance of the Commons with Remix the Commons, the organization that masterminded the Commons Assembly. We were invited to a meeting run by Civic Lab where they showed us the consultation they had been running with citizens in the 18th Arrondissement on the empty space beneath the raised metro railway lines between the Stalingrad and Barbes stops, along the Rue La Chapelle. The space had been a temporary camp for migrants, who were then moved on and the areas fenced off.

The city of Paris administration had then teamed up with the mayoral teams from several arrondissements in the north of Paris to call for ideas about what the space could become. As well as a covered urban promenade and cycle track, could there be more permanent meeting spaces, maybe for eating as well as gathering? How could all ethnic groups be made welcome? This was a space for the imagination if ever I saw one. And that is how I see the Commons: one of the most vibrant, connected and positive spaces for re-imagining what it means to be a citizen of place. Transition needs to be a part of this.

Isabel Carlisle

(isabelcarlisle@transitionnetwork.org)

New EU website here: For Common Goods: a European Parliament working group.

European Commons Assembly here.

Remix the Commons here.

3 Comments

Bravo Isabel, very to the point this article, i hope that movements like Transition en Commons bring back he balance in the world,

kind regard from sunny Frnace

I fully agree that Transition needs to be part of this. As we many things, we are already doing it without naming it 🙂

We all also need to learn more about commons (here’s good resource: http://www.bollier.org/new-to-the-commons) and connect with commoners around us because they are practitioners, like us.

i’m not Indigenous to North America, but i’m not sure they would equate ‘commoning’ to to Indigenous peoples’ caring for ‘precious resources’. i’m curious on why you think this is so. i work for an org. called Great Lakes Commons and i feel we have to re-invent or re-mix many aspects of commoning to align with the decolonial/social justice framework and the massive Indigenous rights resurgence happening now. the word ‘resource’ is very western compared to ‘creation’ or ‘gift’ and even the actions of ‘care’ or stewardship don’t match as well since care is (but isn’t always from a western POV) in reciprocal relationship with the gift of creation…. so much more than what a resource can offer. a very different ethic.

it would be interesting to also think through the progressive position of creating ‘land trusts’ on land that was (and remains) stolen under doctrine, force, and statehood. Indigenous peoples in Canada have self-determination on 0.02% of Canada’s massive land base. how does a land trust work to advance this decolonial movement?

even the concepts of ‘public’, ‘civic’ and ‘democracy’ take on different politics in Canada, the USA, and other settler states. many Indigenous peoples here don’t consider themselves ‘Canadian’ or ‘American’ and the systems, duties, and practices that define this type of ‘citizenship’. are imposed and foreign systems that have created (and continue to create) an immoral level of damage.

i’d love to work with other commons folks interested in aligning commons with decolonization within North America (Turtle Island).

1 Trackback